Did you feel a slight chill during last year’s partial eclipse? This phenomena has been observed by eclipse watchers over the centuries. Thanks to 4,500 citizen scientists across the country, along with meteorologists at University of Reading we now know why. This project was a successful national science activity, stimulating interest from Cornwall to the Shetland Islands, with both scientific and engagement value.

Did you feel a slight chill during last year’s partial eclipse? This phenomena has been observed by eclipse watchers over the centuries. Thanks to 4,500 citizen scientists across the country, along with meteorologists at University of Reading we now know why. This project was a successful national science activity, stimulating interest from Cornwall to the Shetland Islands, with both scientific and engagement value.

The results can be found in papers published in a special ‘eclipse meteorology’ issue of the world’s oldest scientific journal, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A. Alongside the science results there’s also an evaluation report on how the citizen science project was used a schools outreach tool. This paper was written by Dr Antonio Portas, then SEPnet Outreach Officer at the University of Reading’s Department of Meteorology and the other scientists leading the project, Dr Luke Barnard, Prof Chris Scott and Prof Giles Harrison.

The paper gives details on the logistics required in carrying out this type of citizen science project, including details on how they anticipated problems with data collection and solved this through using standardised web forms. This may be of particular interest to those wishing to run similar types of experiments or even replicate this one for the next eclipse across North America in 2017.

Results from the outreach evaluation are also included. In total, 96.3% of participants reported themselves as ‘captivated’ or ‘inspired’ after taking part. The paper also contains a discussion on school selection; 60% of the schools that took part in the experiment lie within the highest quintiles of engagement with higher education. This emphasizes the need for the scientific community to be creative when using citizen science projects to target hard-to-reach audiences.

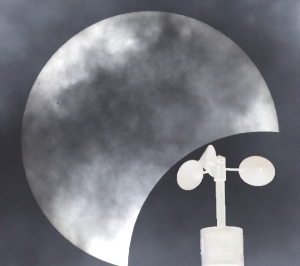

As to the science itself, the project results show that the wind change is caused by variations to the ‘boundary layer’ – the layer of air closest to the ground. Prof Giles Harrison explains: “There have been lots of theories about the eclipse wind over the years, but we think this is the most compelling explanation yet. As the sun disappears behind the moon the ground suddenly cools, just like at sunset. This means warm air stops rising from the ground, causing a drop in wind speed and a shift in its direction, as the slowing of the air by the Earth’s surface changes.”

The outreach evaluation paper can be found here. The analysis of the data collected through the citizen science experiment can be found here. The full special ‘eclipse meteorology’ can be found here.

Did you feel a slight chill during last year’s partial eclipse? This phenomena has been observed by eclipse watchers over the centuries. Thanks to 4,500 citizen scientists across the country, along with meteorologists at University of Reading we now know why. This project was a successful national science activity, stimulating interest from Cornwall to the Shetland Islands, with both scientific and engagement value.

Did you feel a slight chill during last year’s partial eclipse? This phenomena has been observed by eclipse watchers over the centuries. Thanks to 4,500 citizen scientists across the country, along with meteorologists at University of Reading we now know why. This project was a successful national science activity, stimulating interest from Cornwall to the Shetland Islands, with both scientific and engagement value.